As I hit me, I drove through Westlake on the way to visit Nathaniel Anthony Ayers in Nathaniel Anthony’s nursing home.

My God. Have you been 20 years?

It’s hard to believe, but yes.

That year was 2005. As I remember it was noon about winter after the rain. I heard the music from Pershing Square and followed the sound and found the shopping cart next to him and his belongings were full.

So: Mr. Ayers’s violin lacks two strings and tries to return to the track thirty years after being sick and forced him to leave the prestigious Juilliard school in New York. My laptop, while trying to drive a mental health system, met this Cleveland-born prodigy, which allowed thousands of people to raise themselves on the streets of Los Angeles.

Neither of us know where we will go together in the next few years. Go to Disney Concert Hall. Go to the Hollywood Bowl. Go to Dodger Stadium. Go to the beach. Go to the White House. At the beginning and end of a series of operas, the swollen strings and the impact of c-ramming, riding the wave of what Mr. Ayers calls the music of the gods.

“Can you believe we have friends for 20 years?” I told him during my visit a week ago.

He was fixed with a buttock injury and raised his head curiously from the bed. He didn’t do math, but there was no controversy – we took the express train from the 50s to the 70s. He smiled and said that when we met, he was “on the street, homeless, playing the violin with two strings”.

Former President Barack Obama shook hands with Nathaniel Ayers at an event commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 2010.

(White House)

That’s the title of the first column. “A violinist has a world of two stringsbut he is talking about his unshakable reference to music. He played near the statue of Beethoven in Pershing Square for inspiration.

I reminded Mr. Ayers (that’s what I call him, he calls me Mr. Lopez) of his response to the first column I wrote about him. Shortly afterwards, six readers gave him the violin, two others gave him a cello, one donated a piano, and we dragged to a sliding music room with his name at the door, at the Homeless Services Department, now known as People Charres.

Convincing him to spend a year moving indoors, he taught me a lot at that time, mainly about how everyone in his shoes has unique needs and fears, and a complex history of trauma and stigma. Such people often Disconnected, multi-faceted care system.

Through Mr. Ayers, I met countless dedicated civil servants in the field of mental health. They are there every day doing tough, noble jobs that provide comfort and life-changing. But the demand is huge, and it is the complexity of street drugs that some people use for self-drugs, and despite billions of dollars in investment in solutions, progress is often plagued by multiple forces.

Jon SherinWhile many people have done good work, the bureaucracy has undermined innovation and eroded the morale of frontline workers, said the former head of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health.

“We live in a world where people can serve the service regardless of whether it has any impact or not, and billing has become the main agenda for the bureaucracy and everyone.” Psychiatrist Sherin said he had similar frustrations when he was with the Veterans Administration. “We are taking care of the process and we are not taking care of the results.”

Schelling said the goal must be enough housing resources and helpand create a safe living environment that provides what he calls three PS (people, location and purpose).

Over the past two decades, many have stepped up to provide Mr. Ayers with varying degrees of success, and there is no shortage of heartbreak or hope. His sister Jennifer was his conservative, signed by longtime family friend Bobby Witbeck, and so did Juilliard’s classmate Joe Russo. Gary Foster, made the movie “soloist,” Based on me Books of the same namehas served as a member of the board of directors of Mr. Ayers and many others for many years People worry.

Back in 2005, Peter SnyderHe was a Philharmonic cellist at the time and was willing to teach Mr. Ayers. They happened in the apartment he would eventually live in.

After the first column about Nathaniel Ayers, six readers sent him a violin, and two others gave him a cello, one of whom donated a piano.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Adam CraneThen, he worked at La Phil at the time in Los Angeles, opened the door to Mr. Ayers to Mr. Ayers and reintroduced him to the musician community: the pianist Joanne Pearce Martincellist Benhong and violinist Vijay Guptaamong other things, met Mr. Ayers and played music with him.

One night at Disney Concert Hall, Crane and Hong took us backstage after the concert so that Mr. Ayers could be reunited with former Juliad’s classmates Yo-Yo MA.

“Nataniel…had an amazing, life-changing impact on me,” said Crane, who is now in the New York Philharmonic.

“I often talk about the power of music to change life, but I have never experienced it with as profound and passionate as the time I spent in Nathaniel. From the time we first met in 2005, when he played my cello in my office (his joy, and his past training, those years that shine), I have seen Nathaniel’s experience and people whom he relied on, and have developed a family attachment and has developed a family attachment. Love – music for his happiness and survival.”

I knew there was a momentary connection between the crane and Ayers, but I didn’t know the full text until later.

Crane explains: “It shows different not only in our shared love for music, but in our struggle with mental illness. Nathaniel helped shape my understanding of mental illness and the human condition, and he deeply deepened what I mean to music for people.”

A few weeks ago, I visited Mr. Ayers with his former social worker, Anthony Ruffin, who Lost home in Altadena fire In January. Mr. Ayers is not always the easiest client of Rufen – he can resist helping and even fighting. Once, Mr. Ayers “fired” Rufen, just as he “fired” Rufen’s mentor Mollie Lowery. but Rufen is a skilled observer who sees through his mask For the nature of this man, he was inspired by the resilience he witnessed.

“A lot of things happen in the world, and when I meet and talk to Nathaniel, it makes the world look perfect,” Rufen said. “When he talks to me, he always gives me a little bit of insight into life, and I get rid of his humility in existence. Very humble.”

Mr. Ayers has a lot he can complain about. Homelessness has caused his body to lose so many years, and over the past few years, injuries to his hips and hands have prevented him from playing violin, cello, keyboard, double bass and trumpet.

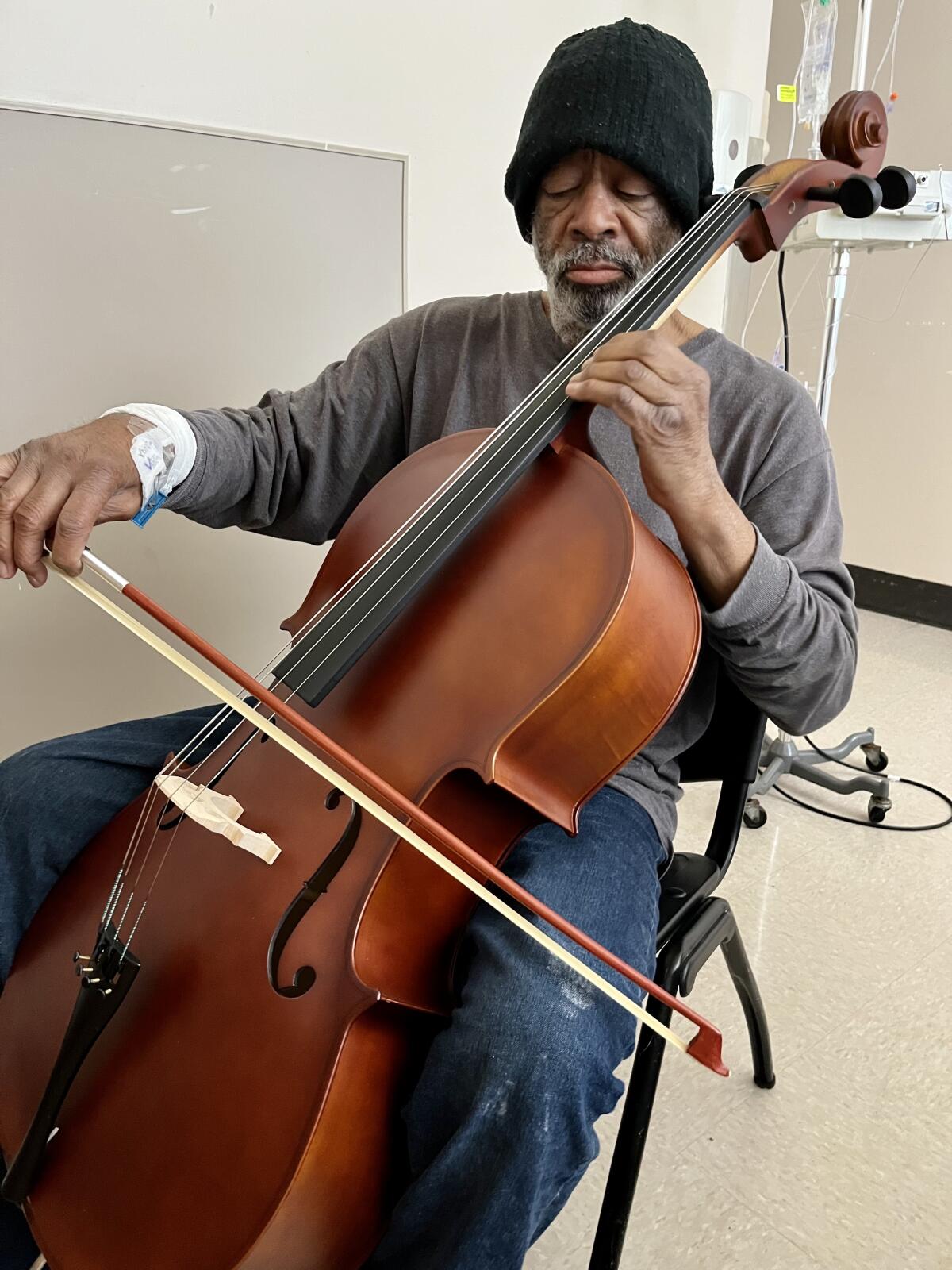

Nathaniel Ayers played cello during his brief tenure in the hospital.

(Steve Lopez/Los Angeles Times)

But in my last visit, when I asked him how he would describe the past 20 years, he didn’t hesitate.

“Very good,” he said happily.

We talked about our Visit the White Housewhen he performed on the 20th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and met with then-Obama, who was wearing a white suit and a high hat at a Hollywood suit store. We talked about his party with yo-yo when the cellist hugged him and said they were brothers in the music.

I remember Mr. Ayers refused to leave my car one night until the last sentence of Sibelius Symphony played on my radio. I remember he said that in his New York apartment he practiced Tchaikovsky’s serenade as he watched the snow outside his window with his skewers on his upright bass. I remember the night on Skid Row, before he fell asleep, he grabbed two sticks with the names of Beethoven and Brahms. He said a stick would scatter them when rats rise from the sewer.

Since our chance encounter 20 years ago, he has given me a deeper understanding of patience, perseverance, humility, loyalty, and love. He reminds us that in addition to the first impressions, stereotypes and boundaries we build, people can also open up humanity and grace to their richness.

When I asked Mr Ayers about his advice, even in all the hardships and disappointments he faced, he pointed to the radio beside the bed, which was always opened on the 91.5 on the FM dial, the home of the music of the gods.

“Listen to music,” he said.

steve.lopez@latimes.com